At the beginning of the month, I attended the chaotic nerd gathering known as 'DragonCon' in downtown Atlanta, Georgia. During my time there, I saw some amazing cosplay, got to peruse aisles of merchandise, and danced with a giant Pickachu whilst dressed as Captain Underpants. But between all that, I sat down with fabled game maker Richard Garriott, known by his handle Lord British, and creator of Ultima.

This guy coined the term MMORPG, so it was a delight to sit down with him and pick his brain on his past and future, both of which proved to be equally fascinating.

Tom: Your father was an astronaut. You’ve been to space yourself, but your most notable series is Ultima; you’re working on Shroud of the Avatar, both of which are fantasy games. What about fantasy attracted you when creating games, when obviously science and sci-fi has played such a deep role in your life?

Richard: You know, if you go back to the earliest Ultima [games], so the late 70’s and early 80’s, they were really hodgepodges of everything I saw around me in life that was inspiring. And so Ultima 1 and 2 both include a medieval fantasy portion of the game, but also sci-fi including space travel. Ultima 2 included time travel, even: you can go back to the time of the dinosaurs or go off into the future and explore the other planets. And so I would say I’m both equally interested in medieval fantasy and sci-fi. If you take great pieces of sci-fi and fantasy, let’s say Star Wars and Lord of the Rings: you could tell either one of those stories in the opposite setting, and it would still be a great story. So I actually think the reason my games have ended up in medieval is frankly a practical, technical reason associated with my journey through development. I started developing on the Apple II computer, which is a pretty primitive computer, and I figured out something which is now called tile graphics. If you remember the maps on early Ultima [games], they were 14 pixels wide by 16 pixels tall images for grass and water, etc. So I sort of invented this top down, scrolling map presentation that worked very well, when that same Apple II didn’t do 3D Star Wars looking stuff very well at all. I just started trending toward the one that I could execute in the most interesting way. But I’m equally interested in both!

Tom: That is clear in your games, and I’m sure Shroud of the Avatar will have some sci-fi tendencies.

Richard: What’s interesting is, it originally started as sort of a steampunk historical future, but at first my core fanbase was like “What are you doing?! We really want medieval!”, and so I kind of hid the steampunky, clockpunky stuff and we promoted the medieval stuff and everybody felt comfortable. Now that everyone’s comfortable, we’re actually putting back in the steampunk and clockpunk. Because after a while we were like “This is too traditional. What can we do to mix it up?” but we had this [steampunk] right here, so we pulled it back in. So yes, we will sort of see a historical future edge to it.

Tom: You were fortunate enough when you were working at ComputerLand to, for fun, create a game called Akalabeth. Your employer thought it would sell, basically said “Do you want to sell this here?” It got into the hands of California Pacific, you made a deal with them, and that’s basically where your career in video games began. Were you interested in gaming and pursuing video games as a career, or since you have so many other interests would you have gone into something else? It just seemed like the perfect storm.

Richard: It was a perfect storm. Akalabeth sold 30,000 copies, I made 5 bucks a piece, that’s 150,000 dollars for a high school senior, and it took me about 7 weeks of after school time. So the return on investment for that game was the best I’d ever had to this day. But it was just obvious that I should do another. My dad’s income as an astronaut was something like 65,000 dollars a year, so I had almost tripled my dad's income with 7 weeks of after school time. So everyone in the family, myself included, said, “Let’s go make another one!” And even I knew I could outdo Akalabeth easily just because I was never meaning for that to be played by anybody else. So instantaneously I was going “I could do way better than that!” No one in the family, including myself, thought of it as a career though because there was no industry! So I thought that this was just something to do for a little bit. In fact, a couple of years later when I was making the decision to drop out of college, which I sort of had to do because I was failing classes, my family was like “Well, of course, you should go pursue that. There’s no college degree for that! But surely this will end. And when it does you can go back to school, finish your degree and go get a real job.” And of course that was 45 years ago.

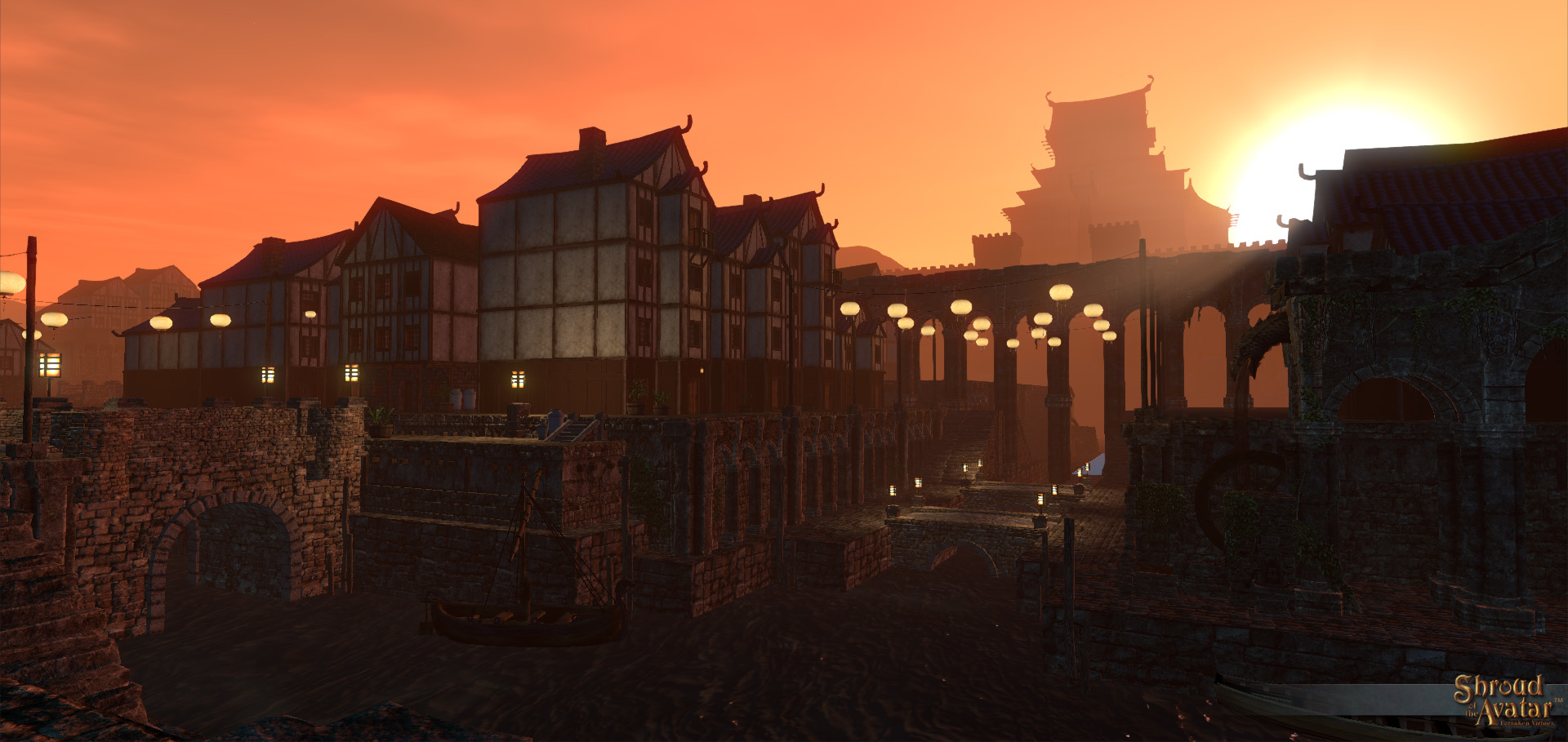

Tom: Shroud of the Avatar is your latest project. That was funded through Kickstarter, with Forsaken Virtues being the first in a series of five episodes. It’s been deemed a spiritual successor to Ultima: in fact, you even said you’d call it Ultima if you had the rights to it.

Richard: Yeah! In fact, every year I give EA a call and say “Look. It wouldn’t be hard to make it an Ultima! You’re not doing anything. We could make a deal. Let’s do it.” And every time I called their executives go “Yeah. That’s a great idea!” And then they shop it around internally, and there’s always some group internally that goes “No. Someday, I’m gonna use it.” And so EA understandably favors their in-house studios, and so the potential deals have fallen apart every time. And so I’ve been very careful to make sure it’s not a derivative work. There're no references in Shroud of the Avatar to names, places, events that happened before. But Shroud of the Avatar is clearly a Lord British, medieval game that includes virtues as a core concept and is not incompatible with anything I’ve done in the past. And therefore, in your own mind’s eye if you don’t want to break the continuity I’m not forcing you to break that as a player.

Tom: So obviously, this is a game that’s coming out soon. A long time has passed since Ultima came out. In what ways is it going to differ from the Ultima games?

Richard: What I find interesting that’s happened since Ultima Online came out in 1997, most role-playing games and especially online RPGs have built themselves on the model of Everquest and World of Warcraft. Very few have attempted to build themselves in the form of Ultima. I think there’s a number of reasons for that. First off, I think to build in the Ultima model is hard, because my devotion to reality crafting beyond what’s necessary is expensive, takes time, and it’s not clear that it pays dividends. It’s just what I like to do. On the other hand, here’s my critique of a generic role-playing game: the first thing you do is you create a character. Since you have lots of detail these days, it might take you 30 minutes to an hour to get it right. And you’re not going to get the chance to do it again! So you want to get it right because you’re not going back. So you spend the first hour doing something, and you don’t even know if you’re going to like the game yet. Yet you’re devoted to doing this preamble. Then when you get in the game it might be very beautiful whether it’s historical or futuristic setting, but as you look around you see the weapons shop, magic shop, the people with the exclamation points over their head to tell you what to do. You go click on one of them, and they tell you to go kill X of these and bring me Y of their pelts or parts. You can look down the street to the edge of town, and there are those first level monsters that you need to go to. When you click on your quest in your quest log an arrow shows up on the map, you walk out to those level 1 things, you farm them for XP, you bring it back, and you repeat till you’re level 2. In which case, the arrow then changes direction and sends you toward the level 2 hunting grounds. Basically, everyone is doing that exact model! I find it relatively brain-dead in the sense that you’re not reading those conversations [with NPCs]. You just click till it goes away because now it’s in the quest log. You don’t really care what’s going on, and there are no decisions you’re making that are really important.

Richard: Now contrast that with what I did in the early Ultima games, which is not repeatable. In the early Ultima games, you had to map yourself. If someone told you that you had to go to the women in the red dress to see her about her necklace, you had to make notes, or you’d forget. And if a week went by since the last time you played, it’d be easy to get totally lost. A lot of these auto mapping, auto conversations, and quest logs: those were made to fix problems that existed in the early days. But I actually think in aggregate they’re the wrong solution. They’ve actually made games mindless. What we’ve tried to do is start where we were in the past and fix those problems, but fix them in a way that leaves you with something that is relevant. For example, there're no exclamation points, there’s no quest log, there're no arrows on the map. When you walk through a town, if somebody wants to tell you something, they point at you and go “Hey, come here! I’ve got something for you!” They’re actively soliciting you rather than just standing there waiting for you. Anything you’re told goes in a journal, so you do have it [written down], but it would still be hard to find those kernels of “Hey, I need you to go find that necklace that was stolen from me.” Instead, if there’s something we might define as a task, no matter how strangely worded it is, you can actually sort by the ones that are tasks that have not been resolved. But by billing it as a task list instead of a quest log, they’re not forced into a similar structure. In quest logs of other games, it has to be “Find X of these at this physical location, acquire Y things from it, and if you return it to me you will get Z dollars in reward,” so all quests in most games have the same structure to fit in the data. We don’t do any of that at all. I think we’re making improvements from days of the past in ways that aren’t offensive to your intelligence.

Tom: That sounds actually really cool! Nonplayable characters actively interacting with you; even that little detail opens up a whole new level.

Richard: And because in my games, there’s day and night, and astronomy and weather, all those things affect what’s happening around you. Only when it’s raining do mushrooms grow, and so in some regions, you literally have to wait for it to rain and then go out in the swamps to find those. If there’s a grave robber, he’s only going to be robbing graves in the middle of the night. He’s not going to do it in the middle of the day! You really have to explore the world with purpose versus just going to the graveyard. You have to go to the graveyard at the right time and/or under the right conditions of weather or astronomy. I think it’s a much more intelligent, participatory experience.

Tom: After several setbacks, you were able to finally achieve a lifelong goal of going up to space. You spent some time there. Officiated a wedding up there, which you know, is crazy. Obviously, that’s a life-changing experience. Did that affect how you created and designed games? Did you return to medium with, I don’t know, an awakening?

Richard: It’s funny, space was the pinnacle experience [of my travels], but the place previously before that I was most awestruck by was the middle of Antarctica. Ice and rock and nothing else sculpted in the most astounding ways. The laws of physics are changed around you, and you’re really in an alien place. There’s a place in Antarctica I was walking: the wind there tends to go from the south pole northward and outward. The hot air rises to the equator, it sinks at the south pole and spreads north. So if you’re on the north side of a mountain range, the wind moves across and twirls on the downwind side. That then sculpts the ice, which is nominally a mile thick, in this big curl. And then you walk in that curl as if it’s a frozen tidal wave. We were standing in this place, which goes on for miles and sort of looks like a Tim Burton movie with the edge dripping snow, and this clear blue ice beside you. It’s this completely surreal, awesome experience. If I tried to 3D model that, it wouldn’t be nearly as awesome. But I can take that feeling away, and figure out how I can provide the player that same visceral emotion. Even if it’s completely cast in a different structure. So yes, I do use them but not in an obvious way.

Tom: Right. Extrapolating that emotional resonance and injecting it in the game. OK. This is a fun question: if you could work on any game series, or adapt an existing franchise into a video game, what would it be and why?

Richard: I have a strange affinity for games like Battlefield 1942 and/or the original Command and Conquer, so I would do something in between there. I know one is a first person shooter and the other is a real-time strategy, but somewhere between those are games that I admire what it took to create them and when I play them I feel like I’m learning a lot. I wish to myself I was able to have the time and skill to produce one of those at a high level.

Tom: Before we wrap up, Shroud of the Avatar is a game that’s been in gestation for a long time. Can you give an update as to where you are in the project?

Richard: It will be 2017 for the episode 1 launch. What we’ve reached now is persistence, and so we’ve quit wiping the player database. Early in development, if we changed fundamentally how many attributes a player has, you kind of have to have everybody start over. And we’ve literally had people playing since it was just a person in a room sitting on a chair. The people that have been with us for a long time, every month they see an amazing amount of progress. The people that have not been playing all along, they come in and go “Hey. This game’s not finished!” but then you have people going “You don’t understand. Last month, it was just a chair in a room, and this month we have combat!” The game as it is, I would say, is very solid for a very short experience. That’s because of the 20 cities that the story threads through, three or four of them are to the quality level we are looking for. The rest are sort of blocked in. But now, for the next four to six months, we’ll be polishing the rest of those cities and fine tuning some other things. The systems work, but they’re not particularly well balanced and some of the trees are not fully fleshed out. So if people join now, and we want more play testers, know that the game is absolutely not ready to be viewed as a final game.

Tom: Sounds excellent! Thank you so much for your time.

Richard: Thank you!